Gladiator (2000): Historical Research (Roman Empire Focus)

Research by: Michael S. Andrews, Social Studies Teacher, Lummi Nation School

Introduction

In 2020, Dave Franzoni, the drafter of the earliest script for the film Gladiator, recalled his experiences in 1972 when he rode a motorcycle across Europe and the Middle East. He reflected on how often ancient arenas would pop up on his journey, all the way through Turkey, and how they must have been ‘...a hell of a franchise’. Gladiator’s origins as an exciting idea based on real history translate well to the film - in many ways, it is authentic and allows viewers to imagine what Imperial Rome could have been like. In other ways, stereotypes, tired tropes, and inaccurate history have further led to a lack of understanding of such an enormous topic like Ancient Roman history. Nevertheless, this research is intended to provide a historical overview of the Roman Empire in the 2nd Century CE with other sections focused on the Imperial Legions, Gladiatorial life, the Emperors of the period, and the future of the franchise.

Note: My research is split up into different bulleted points, which are grouped by theme. Spaces in between bullets and bolded titles indicate a change in topic to make my research more organized/easier to find and utilize.

Section I: The Roman Empire in the 2nd Century Overview

Brief Roman History Pre-2nd Century CE

- According to the historian Varro, Rome was founded among seven hills in central Italy in 753 BCE.

- Romulus, the pseudo-historical founder and first king of Rome, ruled from 753 - 716. He is said to have murdered his brother Remus in the creation of the city

Romulus & Remus suckled by a she-wolf

- At this early point in their history, Rome is not significantly large, important, or renowned. Instead, the 700s see the rise of an Italic people known as the Etruscans. Rome will end up inheriting much of the Etruscan knowledge and art in its early years.

- After years as a Kingdom, the last Roman king Tarquinius Superbus is ousted from power by Lucius Junius Brutus and the Roman Republic is established in 510 BCE. Power is shared by two elected rulers called Consuls, as well as a senate.

- Rome itself is partially sacked by Celtic people known as Gauls after they invade Italy in 390 BCE.

- Rome subdues most of Italy by 281 BCE - one of the final holdouts are the Greek colonies of Southern Italy, in particular Tarentum (Taranto) after they enlist the aid of Pyrrhus of Epirus, one of the many successor kings of Alexander the Great.

- From 264 - 149 BCE, Rome fought three major wars known today as the Punic Wars. The rival maritime Republic of Carthage in today’s Tunisia competed with Rome for influence over the Western Mediterranean. The Second Punic War has passed into infamy thanks to several key defeats on Rome that nearly crippled it. Hannibal Barca nearly turned some important Italian allies of Rome against her, destroying many legions at the battles of Trebia, Trasimene, and Cannae - the latter being one of the most devastating defeats Rome ever suffered.. He had little support from his rivals back in Carthage and ended up retreating back to Carthage, where he was defeated by Publius Cornelius Scipio (later named Scipio Africanus for his victory) in North Africa on the plains of Zama.

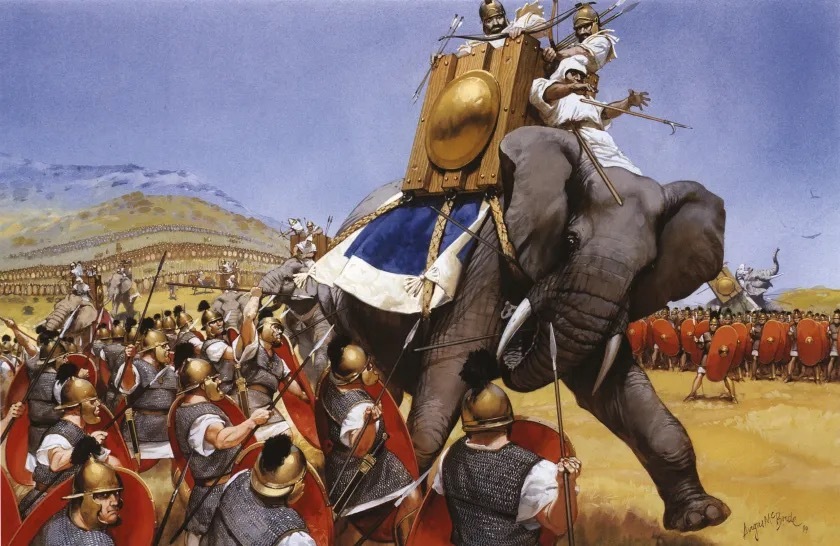

A depiction of the Roman victory over Hannibal at Zama

- All Punic Wars ended in defeat of Carthage, leading to the complete annihilation of the old city in 149 BCE.

- The 2nd century BCE saw Rome defeat two more Successor Kingdoms, Macedon and the Seleucid Empire.

- The final BCE century saw tumultuous political violence and the decline of the Republic. Gaius Marius and Sulla, two of Rome’s consuls, vied for power and resorted to political terror and war - even marching on Rome itself with an army - to maintain unprecedented lengths of political tenureship, including as dictator (originally meant as an emergency power granted to Consuls that allowed full political freedom and power for a set period of time).

- The Roman populace who had any semblance of political power divided into Populares and Optimates - the former focused on the common people and the latter desperate to maintain power for the upper class aristocrats. This era saw the rise of people like Gaius Julius Caesar, Gnaeus Pompeius, and Marcus Crassus - these three dominated Roman politics, creating the First Triumvirate.

Bust of Gaius Julius Caesar

- Crassus is killed while on campaign in Parthia (Persia) and Caesar conquers Gaul illegally, becoming immensely wealthy and powerful. Caesar is able to win over the loyalty of his legions through personal payments made to them and years of fighting by their side. This becomes increasingly distressing for Pompeius who is back in Rome handling the political situation there. Growing concerns rise that Caesar intends to take power for himself violently, as Sulla tried to do decades prior.

- Pompeius attempted to strip Caesar of his power through his governorship over Cisalpine Gaul, which Caesar had greatly expanded by invading and conquering all of Gaul (roughly modern day France). His legions were more loyal to him than to the Senate and People of Rome (SPQR, Senatus Populusque Romanus).

- Caesar crossed the River Rubicon, the boundary that was forbidden to cross with an army. He conducted a civil war that saw the death of Pompey, the destruction of the Republican armies, and his institution as dictator for life. He was assassinated in 44 BCE.

- Caesar’s nephew and adopted heir Octavianus worked together with one of Caesar’s former generals, Marcus Antonius, and brought down Caesar’s assassin’s. They split power between themselves and the former Pontifex Maximus (high priest) Lepidus. Eventually, this Second Triumvirate broke down and helped firmly transition power in Rome to a single man - Augustus Caesar, Octavianus’ new name, with the title of First Citizen (in reality, emperor). 31 BCE is often regarded as the beginning of the Roman Empire.

Statue of Augustus Caesar, formerly known as Octavianus

- The first two centuries of the Empire from the reign of Augustus to Marcus Aurelius are labeled Pax Romana (Roman Peace), where stability was at an all time high.

Roman History, 2nd Century CE

- The period between 27 BCE and 180 CE included several major events and activities that helped us understand the world of Gladiator as we see it during the 2nd Century.

- First, Augustus Caesar reformed the Roman tax system, established a standing army, and began the process of fundamentally rebuilding Rome.

- Oddly enough, Augustus reformed the organization of the Republic by allowing provinces that accepted Roman taxation and military control to freely practice religion and continue local customs that did not directly violate Roman law.

- Augustus instituted a permanent civil service that allowed for mechanisms to be created that investigated corruption and punished provincial governors who sought to exploit their position for personal reasons. This, of course, did not apply to the ruling First Citizen (Emperor).

- The Mediterranean became largely clear of pirates. Trade routes thrived thanks to political stability under the Principate (the royal family) and trade lanes were established to places as far away as India and China.

- Imperial resources were collected to fund large infrastructure projects that were impossible in the previous province-heavy system of the Republic. Just during Augustus’ reign, 50,000 miles of new roads were constructed. Roman aqueducts brought drinking and bathing water into many major cities. Emperor Trajan built bridges and harbors. This further spurred strong, healthy trade routes.

- Arts and literature were encouraged under the empire, especially if they made the Empire look good!

- The “Aeneid” was written during this time by Virgil - providing Rome with another mythical founding from the time of the Trojan War and drawing parallels between Aeneis and Augustus. Horace and Livy also wrote histories during this time.

- Cultural Imperialism was used to assimilate provinces more closely into the Roman sphere of life. Roman hairstyles, clothing, and other cultural highlights spread to the elites of the provinces. This also encouraged them to adopt Roman citizenship and serve in the Senate. The Western regions of the Empire, including Gaul, Spain, and Germania, all took hold of this assimilation rather well. Of course, the opposite is also true - we can thank the Gaulish Celts and Germanic peoples for popularizing pants among Romans, and thus to us!

- Chariot race stadiums, amphitheaters, forums, bathhouses all became common in the larger provincial towns and cities.

- Rounded arches and domes created from Roman concrete (a mixture of “volcanic sand, high-grade lime and small stones or broken bricks”) symbolized the power of the Roman Empire.

- The Coliseum, the Pantheon, the Roman Forum (a central meeting and marketplace of a city), a dozen new temples, a new Senate house, and more were constructed during this time. One of Augustus’ most famous quotes include one related to this construction: “I found Rome of bricks; I leave to you one of marble”.

- The most major flaw of this time period, and of the Principate, was how power was transferred. When an emperor passed, even within Augustus’ familial generation, there was always a risk for unrest, civil war, and conflict. The Pax Romana is a highlight for a particularly stable time of familial and generational succession.

Section II: Imperial Roman Military

Reforms Under Augustus

- The Imperial Roman Army refers to the military forces that operated on land between 27 BCE to 476 CE. For ease of sanity and relevance, we are going to focus on the military during the 1st - 2nd Century CE.

- The Imperial Roman Legion was the most integral part of the military. It was disciplined, effective, conquered new territories and maintained order in those already conquered.

- A single Roman legion numbered around 5,000.

- Under Augustus, the Roman army at first retained its unsustainable size of 50 legions (250,000). This abnormal size was because of the back to back civil wars Rome had experienced during the twilight of the Republic. He brought it back down to around 25 legions (125,000).

- The desire to create a professional army led to further reforms. The Republican era army consisted of volunteer citizen-soldiers who would return to their farms after a conflict no longer needed them. Volunteers replaced conscripts in the early Imperial era. A man still had to be a Roman citizen.

- Roman men of military recruiting age (iunior) was considered 16-46, with legionnaires expected to serve as much as 16 years, with a max of 6 of those years consecutively.

- Augustus reformed this so that 16 years became the standard term of service with 5 years added on for reservists (known as evocati). In 5 CE, this was extended to 20 years. 20 years was not very popular and legions mutinied after Augustus passed to return it to 16.

- Marriage was strictly prohibited for legionaries in the early Principate period (given the number of years required to serve, this makes sense) but by 100 CE, marriage was relaxed as legions began longer, semi-permanent positions on the frontier. Interestingly, this led to many partially Roman children who were not immediately considered citizens but still served in the legions.

- Augustus also reformed the chain of command - the rank of legatus was introduced, creating a long-term commander for each legion. Traditional aristocratic commanders were reduced in their power and a praefectus castrorum (prefect of the camp) handled logistics.

- Retiring veterans could receive a cash discharge bonus instead of land, as state-owned land (ager publicus) in Italy was now insufficient for distribution (not nearly as much land after decades of conscription & war).

- Because of Augustus’ move to create a professional army with longer terms of service, substantial incentives would have to be offered.

- By 5 CE, veterans received 3,000 denarii upon discharge (about 13 years’ gross salary for a legionary), funded by inheritance (5%) and auction (1%) taxes into the aerarium militare (military treasury).

- Veterans were still offered land in new Roman colonies on annexed frontiers, leading to problems among Italian veterans who were then forced to either settle far from home or forfeit their gift of land.

- The Roman veteran colony system was vital for controlling newly conquered na Romanizing provinces, continuing until 117 CE. By 60 CE, local recruits became the majority, reducing the relevance of land grants for Italian veterans.

- Several improvements were made by Augustus that would aid in tactical flexibility and survival rates of legionnaires. 120 cavalrymen were attached to each legion, apparently a substantial increase from the very low or non-existent numbers of the Late Republican era. Lorica segmentata, one of the most infamously iconic pieces of Roman military wear, was introduced by Augustus by 6 BCE. The scutum, a rectangular shield, replaced the old oval shields of the Republic era.

An example of a fully equipped imperial legionnaire during the time of Marcus Aurelius

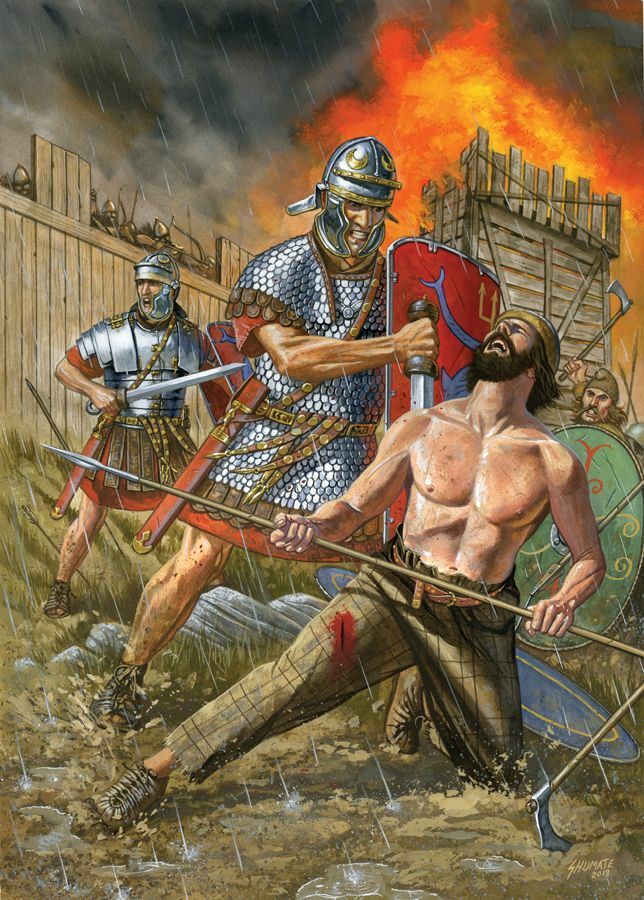

Imperial Roman legionaries defeating Germanic enemies

Auxilia

- Augustus had grand plans to significantly expand the new Empire. This includes domination all the way to the Elbe and Danube, and to North-Western Spain.

- The Republic had used a smattering of irregular, somewhat disorganized and dubiously reliable native, auxiliary, mercenary, and allied forces to assist the legions.

- Non-citizen subjects (peregrini) outnumbered Roman citizens 9 to 1 in Augustus’ time. Augustus started recruiting these into cohort strength (around 500) to form the non-citizen auxilia (meaning “supports”).

- These troops were to serve as a complement to the legions. Early on, these were drawn ethnically, meaning some legions were called cohors V Raetorum (5th cohort of the Raeti), showing that this cohort was made up of people from the Raeti people of the Alps in modern-day Switzerland.

An example of an individual recruited into the auxilia

Praetorian Guard

- A proto-imperial guard served the proconsuls of the Republic under the name cohors praetoria, named after the commander’s tent. Augustus evidently decided that such guards should be increased to a Legion-sized group and renamed praetoriani (“soldiers of the imperial palace”), potentially to dissuade even more civil strife and usurpers when the military was on campaign.

Praetorian Guard out on campaign

- The Praetorian Guard was established also to protect the emperor and his family, Palatine Hill/the Palace, accompany the Emperor on campaign as a bodyguard unit, and defend the imperial government as an institution.

- What made the Praetorians especially unique in the military was their pay (triple the rate of the average legionnaire) and their allowance to carry weapons in the borders of the city of Rome - forbidden in the Republican tradition and the cause of many such civil wears that occur late in the Republic’s history. They were not to wear armor or carry weapons visibly, however.

- An interesting note - there was also an Imperial German Bodyguard (Germani corporis custodes) recruited almost exclusively from a tribe called the Batavi at cohort strength to guard the imperial family even more closely.

- Sejanus, the prefect of the Praetorian Guard under the emperor Tiberius, was one of the first to use his power in the guard to exploit his position within the power structure of Rome. He even poisoned Tiberius’ son Drusus, and nearly succeeded in being named heir apparent to Tiberius until his plot was discovered and Sejanus was killed.

- The Praetorians were very unpopular with the Senate and people of Rome. They were also famous as king makers. Sometimes, they assassinated emperors in order to put somebody in charge who would benefit them directly. Weirdly enough, they sometimes even assassinated emperors they put in charge themselves - like in the case of Galba - and replaced them until they found a more agreeable leader.

Section III: Gladiatorial Life

"He vows to endure to be burned, to be bound, to be beaten, and to be killed by the sword."

The gladiator's oath as cited by Petronius (Satyricon, 117).

Origins

- The origins of gladiatorial combat are murky. Some believe they started as an Etruscan activity, others believe them to be Campanian.

- Archaeological evidence from the old city of Paestum in Campania from the 4th century BCE shows tomb frescoes of pairs of fighters clashing during funerals. These funeral “games” may also originate from an even earlier Greek tradition in Southern Italy during the 8th century BCE.

- Campania also seems to be the earliest place to find ludi, or gladiator schools.

- Livy writes that the first Roman gladiatorial games occurred in 264 BCE, in the very early stages of Rome’s first war with Carthage. A rich Roman citizen honored his father by having three pairs of gladiators kill each other in the Roman cattle market.

- This is described as munus (a gift). For a manes (ghost or shade) of the dead ancestor by the descendent.

- Gladiator types began development during the Second Punic War, where the most popular and frequently mentioned type was the Samnite, named after one of Rome’s most famous enemies and a group that aided Hannibal during his invasion of Italy.

“The war in Samnium, immediately afterwards, was attended with equal danger and an equally glorious conclusion. The enemy, besides their other warlike preparation, had made their battle-line to glitter with new and splendid arms. There were two corps: the shields of the one were inlaid with gold, of the other with silver ... The Romans had already heard of these splendid accoutrements, but their generals had taught them that a soldier should be rough to look on, not adorned with gold and silver but putting his trust in iron and in courage ... The Dictator, as decreed by the senate, celebrated a triumph, in which by far the finest show was afforded by the captured armour. So the Romans made use of the splendid armour of their enemies to do honour to their gods; while the Campanians, in consequence of their pride and in hatred of the Samnites, equipped after this fashion the gladiators who furnished them entertainment at their feasts, and bestowed on them the name Samnites.”

Livy 9.40. Quoted in Futrell 2006, pp. 4–5 (Wikipedia)

- Roman gladiators combined several key themes and activities, from the early funereal and sacrificial elements to the later (and more appropriate for this research) theatrics of the Gladiator show. Exotic, well armed, often barbarian peoples shown to be dominated by Roman might and power in mock battles.

- As Roman conquests expanded, more and more tribes, peoples, and states were included on the list of “acceptable” enemy groups to use as pretend foes in gladiator games.

Expansion

- As mentioned, the Punic Wars provided a crisis that Rome had never seen before on that scale, especially the Second Punic War. Thus, munera gladiatoria helped to raise morale - as a result, they became more extravagant, more numerous, and way more common.

- Gladiatorial games were still very much tied to Roman familial bonds, ancestor worship, and often connected to food distribution to those attending - a hold over from previous Campanian traditions.

- 105 BCE saw the first state-sponsored “barbarian combat” by the consuls of the year. It began as a training program for the military but proved so popular that gladiatorial games expanded from private to public through major religious festivals.

Peak

- Gladiatorial games were truly the professional sports world of the Roman era. They became intensely competitive, political, and provided opportunities for advertisement and sponsorship.

- Sponsors, usually private citizens, would spend a large amount on gladiator games, but offered opportunities for them to self-promote for whatever purpose they might decide to put forward.

- Trainers, owners, old and new politicians could benefit greatly from hosting or sponsoring extravagant games.

- Some private citizens might even postpone the honoring of their ancestor’s death to election season so they could line it up and benefit their election chance.

- Gladiators during the time of the Late Republic would allow aristocrats to use them as political muscle.

- Julius Caesar capped the number of gladiator pairs a sponsor was allowed to keep in the city of Rome to 320. This was due partially to growing Senatorial concern that Caesar was trying to rule through force and because the revolt of Spartacus was in recent memory.

- Augustus took over control of the games and formalized them as both civic and religious duties. Augustus limited the public expenditure on gladiators, making the official max of 120 gladiators, and a ceiling cost of 25,000 denarii.Meanwhile, the games would gradually be more associated with the developing imperial cult and the max ceiling for those games could be a whopping 180,000 denarii.

- In 108 - 109 CE Trajan utilized 10,000 gladiators and 11,000 animals over a 113 day period to celebrate his victories over the Dacians on the Danube River.

- Gladiator games in the empire quickly became a way to further public recognition and respect for the ruler at the time.

- Interestingly, Marcus Aurelius attempted to make gladiatorial games less deadly. He required gladiators to fight with dull swords so they could not kill each other, for example. He attempted to curb the influence that resulted from pouring money into the games - but, after his death, his son Commodus completely ignored or reversed these attempts.

The Orders of the Games

- Well before a game actually started, the games were advertised very much like how games are advertised now. Billboards went up sharing the date, the reasons why the game was happening, the number of paired gladiators being used, and the venue. Luxuries, like food and music, were advertised as well.

- There was a standard of sorts that each game would follow in the imperial period. Lictors who bore fasces came into the arena first, bearing the power of the editor, the magistrate or head of the games, followed by trumpeters (tubicines). These were followed by images of the gods who would witness the events, followed by a scribe to record what happens. A man then carried a palm branch in to signify the victors. The magistrate editor came in with people who carried the arms and armor that would be used for the fight. Finally, the gladiators themselves entered.

- Beast hunts (venationes) and beast fighters (bestiarii) were often the first to begin the entertainment. Executions of noxii could sometimes be condemned to fatal reenactments based on Greek and Roman myth. Gladiators were not often involved in these executions, as the dignity of a fair fight was far more valuable. Music, followed by mock fights, carried forth into the final games.

- Bouts lasted 10-20 minutes, with certain classes of gladiator like the retiarius would tire less quickly than others. The most costly to train and fight were often those with complementary fighting styles. Match winners sometimes had to fight another opponent as an unplanned fight brought forth by the editor, yielding two combats for the cost of three, not four, gladiators. Those reluctant to fight were whipped or goaded with hot iron.

- Killing an enemy, especially among those experienced and well trained, was not preferred. Many gladiators made their fame and livelihood off of bloodless, bravado and dramatic combat. Referees, often former gladiators themselves, could allow rest periods, cool down periods, or a rub-down between fights or even in the middle of a fight. Music was used during the most climactic moments of a fight.

- Overcoming or killing an opponent ended a match. Fighters who went above and beyond may receive a payment from the crowd, while those who were condemned may even be emancipated. A gladiator could acknowledge defeat by ad digitum, or lifting a finger. Sparing gladiator’s lives became more commonplace as the imperial period progressed. When emperors like Caligula and Claudius, for example, refused to spare popular gladiators, their own popularity fell. Custom became the crowd that would decide if a gladiator lived or died.

- The editor signaled the choice of life or death by use of the thumb. “With a turned thumb” is about all we have to know what the editor used as a signal, which is just a bit too imprecise to guess at what direction meant what.

- Sometimes, events did not always play out according to the rules:

“Once a band of five retiarii in tunics, matched against the same number of secutores, yielded without a struggle; but when their death was ordered, one of them caught up his trident and slew all the victors. Caligula bewailed this in a public proclamation as a most cruel murder.”

Suetonius. Lives, "Caligula", 30.3.

The Gladiators

- Trade in gladiators was empire-wide and supervised by imperial authority. The military success of the empire led to a steady supply of prisoners who could be used as gladiators. Ex. large numbers of Jewish prisoners after the Jewish revolt were sent to Rome. The strongest of these prisoners were allowed to “redeem” their honor having been defeated on the battlefield.

Although gladiators began named after the enemies of Rome, they gave way to specific classes of gladiators. Each was trained to specifically fight one or more types of gladiator classes. These are a handful of the 30 or so types of gladiators:

Retiarius (“net”): Used a large net and a trident. Would use the net to entangle opponents before finishing them off with the trident. Was the least armored of the gladiator types, wielding only an arm guard and a loincloth.

Murmillo (“wall”): Used a large, scutum shield and a gladius. Much more defensive style of fighting, wore a mail skirt, armor on the sword arm, and a visored helmet.

Thracian (Thrax): Named after the Thracian people of the Balkans (from which Spartacus came from), armed with a curved sword called a sica. Wore helmets with visors, armored on the sword arm, and held a small rectangular or round shield.

Secutor (“follower/chaser”, originally the Samnite): Carried a short sword, gladius, or dagger. Protected by a heavy shield. A distinctive helmet with two eye holes. These were expected to win quickly lest exhaustion take hold of them. Commodus fought 735 times in the arena as a secutor.

Provocateur: Engaged in verbal taunts with the enemy, utilized psychological tactics to provoke an opponent. Wore a full suit of armor, rectangular shield, and a gladius.

When the Pax Romana era came around, slaves and paid volunteers made up most gladiator stock as fewer prisoners were coming in.

Contrary to popular culture, gladiators were not overwhelmingly forced or slaves. Many poor or non-citizens would gain access to regular food, a steady job, and an attempt to make a name for themselves. Gladiators often kept the money won during a match. The emperor Tiberius even offered money to retired gladiators to come out of retirement and fight in the arena again, presumably because of their popularity.

From the year 60 CE, female gladiators appeared on the scene, but the Romans saw these more as exotic, entertaining, or even absurd to the point where it was amusing to see them in the arenas. Roman masculinity was intense and rigid, so much so that various emperor’s attempts to include women in both gladiatorial combat, olympics, and other athletics usually led to crowd ridicule and eventually the banning of women altogether from these events.

Gladiators were given a banquet the night before a game.

The games featured two types of people that were essentially given a death sentence: the noxii, those who would be executed, and the damnati, who had a chance to survive.

The list of emperors who actually participated in the arena, publicly or privately, with minimal risks, included Caligula, Titus, Hadrian, Lucius Verus, Commodus, Caracalla, Geta, and Didius Julianus.

None were as fanatically involved in the gladiatorial games as Commodus. Styling himself as Hercules reborn, he would win premeditated fights with wooden swords. He would demand Rome’s elite bear witness. He is said to have killed 100 lions in one day, almost certainly from the safety of an elevated wooden platform and wielding a bow and arrow. He cut the head off of an ostrich and wiggled its bloody head and neck, gesturing at the Senate as if they would be next. He also took out a stipend from the public funds as reward for his “services”.

For a really interesting look at modern day gladiator reenactment, see the following video: Gladiator fights - Provocatores, Thraex, Murmillo, Retiarius, Secutor - ACTA

Section IV: Emperors

Julio-Claudian Dynasty (27 BCE - 68 CE)

- This dynasty is also known as the Augustan Dynasty. It marks the transition from Republican leadership to the Principate.

- Augustus, Tiberius, and Claudius were highly stable emperors. Caligula and Nero are famously inept or deranged examples.

- Yet, the imperial system did not collapse with this family. Once Nero died, the transition from the Julio-Claudian Dynasty was messy. What is now called the “Year of the Four Emperors” (69 CE) when Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian fought for control. Vitellus won, and led to the next series of emperors.

Flavian Dynasty (69 - 96 CE)

- Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian all marked their rules during this time.

- Mt. Vesuvius erupted and destroyed Pompeii and Herculaneum during Titus’ reign. Jerusalem was destroyed at this time as well, and the construction of the Coliseum (its true name being the Flavian Amphitheater) was completed during this time.

Nerva-Antonine Dynasty (96 - 192 CE)

- The Nervan dynasty was characterized by Nerva, Trajan, and Hadrian. The Antonine Dynasty was characterized by Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius, and ends with Commodus.

- Nerva adopted his successor, Trajan, which was a first for the imperial line. Trajan is credited with the greatest military expansion in Roman History.

- Hadrian rebuilt the Pantheon, the temples of Venus and Roma, and constructed Hadrian’s Wall in Britannia.

- Marcus Aurelius ruled with a co-emperor, Lucius Verus, from 161 to 169 CE before he continued his sole reign until 180 CE.

Marcus Aurelius with his co-emperor, Lucius Verus

- Lucius Verus marked the first time the Roman Empire was ruled by two emperors.

- Verus’ reign as co-emperor was mostly preoccupied with the Parthian Wars, which he took the lead on.

- His reign coincides with the Antonine Plague, seemingly introduced because of the Eastern campaigns.

- In Gladiator, Lucilla’s son is named Lucius Verus II, after his father and Lucilla’s husband, apparently the Lucius Verus emperor we discuss here. All of Lucilla’s children died very young - including Lucius Verus II, who died even before his uncle Commodus became emperor.

- Aurelius was a stoic and wrote a book called Meditations - which contributes to our great understanding of ancient stoicism more than any other material we have recovered so far. It was written during the campaign between 170 and 180, and describes how to use nature as a guide to preserve one’s own equanimity during conflict.

- Aurelius was an effective military commander. Under his reign, the Empire defeated a resurgent Parthian Empire (a potent dynasty in Persia that earlier had killed off Marcus Crassus and defeated Marcus Antonius).

- He fought the Germanic tribes substantially during his reign - these tribes included the Marcomanni, Quadi, and the more Eastern Sarmatians from the Steppe.

- The Marcomannic Wars in particular were successful - but Germanic tribes were never subdued completely and would continue to be a complicated frontier until the decline of the Empire. Parthia, likewise, bounced back quickly after the sacking of their capital, Ctesiphon.

- From the reign of Marcus Aurelius on, invasions from north of the Danube became more commonplace. Marcus would spend the last decade of his rule constantly defending or leading offenses against the tribes along the Danube.

- The Marcomanni and the Quadi invaded all the way into Northern Italy, besieged Aquilea, and were confronted by Marcus Aurelius and his co-emperor Lucius Verus, who died shortly thereafter. By 169 CE, Marcus was beset by a significant and powerful invasion.

- A great plague had been troubling Rome before and during this invasion, making raising taxes so difficult that Marcus Aurelius was auctioning off his own assets to raise funds for war. In 170, Marcus suffered a defeat and some invasions from these germanic peoples went as far south as the outskirts of Athens.

- From 172-175, Marcus conducted significant military campaigns in the territory of the Marcomanni, and then the Quadi.

- Marcus was surprised by a revolt of one C. Avidius Cassius, who had served with distinction in Lucius Verus’ campaigns against the Partthians. He declared himself emperor in the east, and nearly took the Roman east for himself before he was assassinated by a centurion. Marcus took this seriously, and left the Danube until 178.

- During this trouble in the east, Marcus seemed to be accepting his death was coming soon as he granted more and more imperial power to his 14 year old son, Commodus.

- Marcus’ final plans to create provinces across the Danube in the territory of the Marcomanni and Quadi were cut short, as he died on campaign in 180 CE.

Commodus

- For the first three years of his reign, Commodus ruled as co-emperor with his father, Marcus Aurelius. Commodus has the honorable mention of being considered the end of the Pax Romana and the end of the Roman imperial golden age.

- Commodus’ reign was marked less by military conquest and victory. Internal intrigues became more frequent and this culminated in a cult of personality deifying Commodus as a god. He avoided managing the empire and gave these tasks to other, trusted chamberlains. But attempted conspiracies and coups led to Commodus becoming more dictatorially involved in the affairs of the empire.

- Evidence suggests that although the Senate was not pleased with Commodus, the military and common people seemed to like him.

- Commodus performed as a gladiator during his reign. He staged and took part in theater antics - killing animals from above with a bow and arrow. Combatants he fought would purposely submit to him when fighting.

- Commodus declared himself the new Romulus in 192 and began to develop a connection between him and the Greek hero Hercules by commissioning a statue of him wearing a lion pelt and holding a club just outside the Coliseum. He renamed Rome to Colonia Lucia Annia Commodiana.

A bust of Commodus depicted as Hercules

- The month of November in 192 saw Commodus kill hundreds of animals a day and win Gladiator matches at night. A list was found indicating those Commodus wanted executed, and some on the list conspired to kill him. When poisoning failed, he was strangled by a professional wrestler named Narcissus in a bathtub.

Section V: The Third Century CE (Gladiator II)

A note on the Main Character, Lucius Verus II

- Lucius Verus II, in the film, is apparently the son of the previous film’s protagonist, Maximus. As stated above in the Emperor's section, Lucius Verus was co-emperor to Marcus Aurelius, and died from plague. His namesake died very young, before his uncle Commodus could even become emperor.

- The film surrounds (and compresses) events in the early 200s CE. Lucilla is a surprise to see, as she was executed in 182 CE for conspiring to overthrow Commodus.

- What is interesting is after Lucius Verus’ death in 169 CE, Lucilla married general Tiberius Claudius Pompeianus, and had another son with him - Lucius Aurelius Commodus Pompeianus. This son did survive into 211 CE, when Gladiator II takes place. He may have been killed by Caracalla, but we are not sure.

- Finally, one of the real-life characters that Maximus is based off of is none other than Tiberius Claudius Pompeianus!

The Emperors

- Commodus’ death did not return the Empire into a Republican form of government - in reality, it sparked another civil war called the “Year of the Five Emperors.” (193 CE)

- Septimius Severus emerged victorious out of this civil war. In 197 CE, he began campaigns in both Parthia and in the Northern part of Britannia. In these campaigns, he brought with him his two sons - Caracalla and Geta. Caracalla was named co-emperor in 198 CE, and Geta waited until 209 CE to be granted the same title. Septimius Severus died in 211, whereas the brothers gained joint control over the empire .

Septimius Severus, Flavia Domna, Caracalla, and Geta. Notice Geta’s face has been scrubbed out

- Septimius Severus is an interesting character as he and his sons originate from North Africa. Their mother, Julia Domna, was originally from Syria. It would have been nice to see this mixed heritage reflected in the actors within the film.

- Historically, Geta is presented as the more civil of the two brothers. Caracalla was more concerned with glory in the military and battle. 10 months into their reign, Caracalla had Geta murdered by centurions.

- Geta’s murder was always justified by Caracalla himself. Some historians claim that Caracalla was justified in his brother’s murder, citing the fact that Geta was treated differently by their father, Septimius Severus (being declared co-emperor after Caracalla for example). I found this particular argument a bit strange, but further research indicated that both brothers lived in near constant suspicion of one another leading up to Geta’s assassination. The brothers lived in separate halves of the Imperial Palace, ate meals separately, and even attempted to split the Roman empire in half to rule separately, but this was rejected by their mother (who seemed to be the only one keeping the peace). The implication is that Geta may have been just as likely to have attempted fratricide - but his brother got to him first.

- Caracalla was the one who committed fratricide and damnato memorie (condemnation of memory), as well as proscriptions (hit lists that were meant to purge supporters of a recently assassinated rival). However, as stated above, Geta could have just as easily been the one to kill Caracalla if given the chance. This is despite yet other historians and sources claiming Geta to be the calmer, implicitly more rational of the two.

- This murder of Geta, followed by his scrubbing from the official record, is often the focus of Caracalla. Caracalla also passed one of the most significant pieces of legislation related to citizenship - an edict that granted all free men in the boundaries of the empire citizenship. The baths of Caracalla were created during this time as well, featuring baths of varying temperatures.

- Caracalla suffered a rather unflattering ending himself - he was stabbed in the back on the side of a road while on campaign urinating. This was caused supposedly by the orders and machinations of one Macrinus (played by Denzel Washington in the film).

Macrinus

- Macrinus is shown to be a gladiator trainer formerly enslaved by Marcus Aurelius, but there is no historical evidence to back this up.

- Macrinus was born in Algeria to a wealthy equites (knight) family, right below the Senatorial class. He was a lawyer before he rose to prominence as the head of the Praetorian Guard, and eventually took over from Caracalla for an entire year as emperor - the first time a non-senatorial person, considered lowly, became emperor.

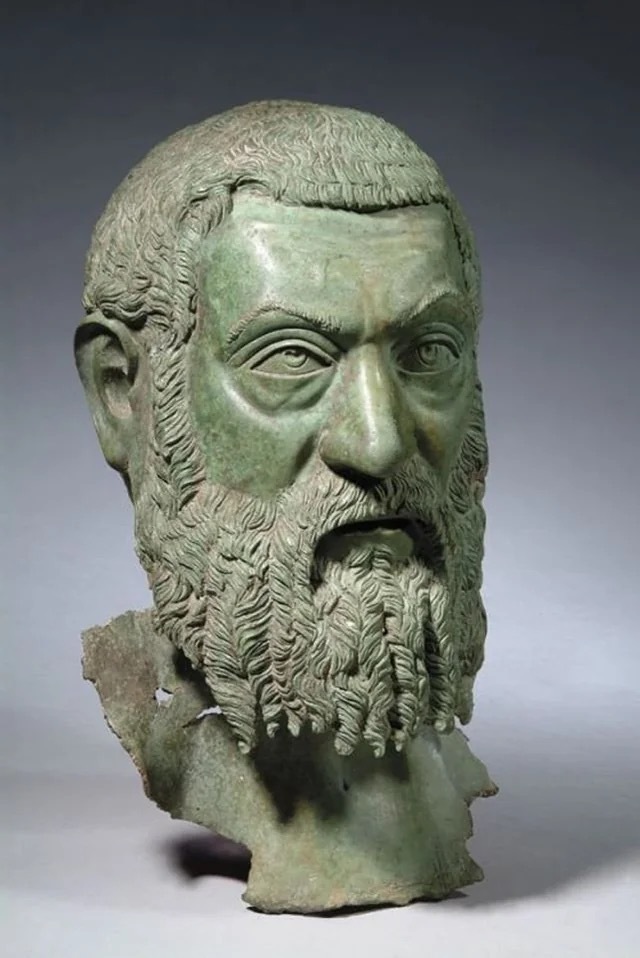

A bust of Macrinus

- Instead of conducting violence to settle foreign policy, Macrinus utilized diplomacy to settle disputes on the frontier. His reduction of pay for new recruits caused his legions to betray him, kill and decapitate him and his son in 218 CE, and send their heads to the new emperor Elagabalus.

Colosseum Events

- Naval battles likely did happen within the Colosseum, but this is not confirmed for sure by historians.

- Called naumachia, these were often staged depictions/reenactments of famous naval battles. Julius Caesar is the earliest known creator of these battles, followed by his successor Augustus. None of these were held in an amphitheater. In fact, Claudius held one in a pre-existing lake, with 100 ships and 19,000 men.

- Nero was the first to host one inside of an amphitheater. Emperor Titus & Domition both hosted naumachia within the Colosseum between 80-85 CE, however the dimensions of a Colosseum compared to the man-made basins and lakes used previously was small. Manoeuvring was likely difficult if not impossible - ships may have been severely scaled down, immobile, and/or completely stationary platforms meant to model ships.

- This leaves Gladiator II’s depiction a bit difficult to accept, thanks mostly to the previous film. It is difficult to understand how the Romans would have flooded the Colosseum after the creation of the substructure underneath, already shown off in the original. The last known naumachia was in 85 CE under Domitian, well before both Gladiator films and before the substructure was built.

- The inclusion of sharks is a stretch. Not that Romans did not know about sharks, but there are no records of utilizing them during the mock naval battles. Animals were always a part of the games, but a man riding a rhinoceros is, likewise, very unlikely.

Conclusion - My Commentary on the Research

Overall, this research could have ballooned even more than it already has. Gladiator is such a great movie not necessarily for its historical accuracy, but in many ways it is historically authentic where it can be while fictionalizing the story. There are plenty of great arguments that say the film did not need to make up a lot of its plot as the real life history is already very dramatic. However, for what it is worth, the film highlights a number of key Roman historical events and activities and brought the interest back to life in the public.

In doing this research I was overwhelmed with just how much information we have around Gladiators, their life, their status, and the history of the Roman emperors and their families. I highly recommend using this research as a jumping off point for your own interest in Roman history.

I can only hope that Gladiator II retains an air of historical authenticity and does not delve too much into excess for the sake of higher stakes in a sequel. Pray to Jupiter Optimus Maximus that it serves the story well!

I hope this research proved useful for you, and I look forward to listening to the episode!

Michael Andrews

Bibliography

Section I: The Roman Empire in the 2nd Century Overview

BBC. (2014). History - Julius Caesar. BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/caesar_julius.shtml

Boatwright, Mary T.; et al. (2012). The Romans: From Village to Empire (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 31-32. ISBN 978-0-1997-3057-5. OL 25033142M

Bury, John Bagnell (1889). History of the Later Roman Empire. MacMillan and Co.; Rome: The Conquest of the Hellenistic Empires Archived 1 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine by Richard Hooker. Washington State University. 6 June 1999

(Intro) Falk, Ben (May 5, 2020). "'Gladiator' at 20: Creator David Franzoni on the film's journey from 'Easy Rider' homage to Oscar hit (exclusive)"

"Five Good Emperors". www.britannica.com. 10 June 2024.

Haywood 1971, pp. 376–393; Hooker, Richard (6 June 1999). "Rome: The Punic Wars". Washington State University.

Livius, Titus (Livy) (1998). "Book II". The Rise of Rome, Books 1–5. Translated by Luce, T.J. Oxford World's Classics. ISBN 978-0-1928-2296-3.

Mackay, Christopher S. Ancient Rome: A Military and Political History. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Pyrrhus of Epirus (2) Archived 14 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine and Pyrrhus of Epirus (3) Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine by Jona Lendering. Livius.org.

Richard Miles Carthage Must be Destroyed 175-176.

"Rome: The Punic Wars". Washington State University.

Syme, Ronald (1939). The Roman Revolution. Oxford University Press. pp. 3–4.

Section II: Imperial Roman Military & Their Enemies

Andrews, Evan. “8 Things You May Not Know About the Praetorian Guard.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 8 July 2014, www.history.com/news/8-things-you-may-not-know-about-the-praetorian-guard.

Cassius Dio, Roman history (transl. by E. Cary, 1968). Loeb Classical Library. Harvard

University Press and William Heinemann, Cambridge, Mass. and London.

Fields, Nic, and Duncan Anderson. The Roman Army: The Civil Wars 88-31 B.C. Osprey, 2009.

Tacitus, Annals, Book IV.

Wiseman, T. P. “Caesar, Pompey and Rome, 59–50 B.C.” The Cambridge Ancient History, IX, 24 Feb. 1994, pp. 368–423, https://doi.org/10.1017/chol9781139054379.013.

Section III: Gladiatorial Life

Barton, Carlin A. (1989). "The Scandal of the Arena". Representations (27): 27, 28, note 33. doi:10.2307/2928482. JSTOR 2928482. (subscription required)

Barton, Carlin A. (1993). The Sorrows of the Ancient Romans: The Gladiator and the Monster. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. 27-28, 66. ISBN 069105696X.

Futrell, Alison (2006). A Sourcebook on the Roman Games. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. 4-7, 48, 85. ISBN 1405115688.

Gibbon, Edward; Womersley, David (2000). The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. New York: Penguin. 118. ISBN 0140437649.

Grout, James. “Venationes: Hunts.” Encyclopaedia Romana, 1997, penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/gladiators/venationes.html.

Kyle, Donald G. (2007). Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. 287, 313. ISBN 978-0631229704.

Livy. The History of Rome. 9.40.

Mouritsen, Henrik (2001). Plebs and Politics in the Late Roman Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 97. ISBN 0521791006.

Potter, David Stone (2010). A Companion to the Roman Empire. West Sussex, UK: Blackwell Publishing Limited (John Wiley and Sons). 407. ISBN 978-1405199186.

Suetonius. Lives, "Tiberius", 7 Archived 10 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

Vernel, Chris. “Gladiator Fights - Provocatores, Thraex, Murmillo, Retiarius, Secutor - ACTA.” YouTube, YouTube, 25 Nov. 2020, www.youtube.com/watch?v=0gf6si_wFyY.

Welch, Katherine E. (2007). The Roman Amphitheatre: From Its Origins to the Colosseum. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 16-19. ISBN 978-0521809443.

Wiedemann, Thomas (1992). Emperors and Gladiators. London: Routledge. 33. ISBN 0415121647.

Section IV: Emperors

Bowman, Alan K.; Champlin, Edward; Lintott, Andrew, eds. (1996). The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume X: The Augustan Empire, 43 B.C.–A.D. 69. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 50-58. ISBN 978-0-5212-6430-3.

Mackay, Christopher S. Ancient Rome: A Military and Political History. Cambridge University Press, 2007. 179-236.

Tellegen-Couperus, Olga (2002). A Short History of Roman Law. Routledge. 76. ISBN 978-1-1349-0801-1.

Section V: The Third Century CE (Gladiator II)

Cassius Dio, Roman History 78.4

Herodian, History of the Empire from the death of Marcus, IV., p. 144

Lerolle, Maxime. “Who Was Caracalla, the Cruel Emperor of Gladiator II?” CNRS News, 12 Nov. 2024, news.cnrs.fr/articles/who-was-caracalla-the-cruel-emperor-of-gladiator-ii.

Empire-Builders. “Before You Watch Gladiator II—Get the Real Story First.” YouTube, 2 Nov. 2024, www.youtube.com/watch?v=9YY8ZId2jqQ.

Lochun, K. (2024, November 15). Sharks in the Arena? Gladiator II’s Real History and Historical Accuracy Explained. HistoryExtra. https://www.historyextra.com/period/roman/gladiator-ii-real-history-true-story/

Solly, Meilan. “The Real History Behind Ridley Scott’s ‘Gladiator II’ and Life as a Fighter in the Ancient Roman Arena.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 21 Nov. 2024, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-real-history-behind-ridley-scotts-gladiator-ii-and-life-as-a-fighter-in-the-ancient-roman-arena-180985494/.